Watershed:

The area drained by a river and its tributaries; all runoff heading for the same outlet.

The drizzle and low-hanging cedar and hemlock impeded my view of the winding over-grown trail on the south side of Carkeek park. I was alone except for the sporadic appearance of slow-moving runners and walkers. They wore a white patch with numbers on their pants at thigh level. What sort of contest could it be, I wondered. At the rise above the railroad track and Puget Sound a pair of young women approached wearing pink tutus. Their numbered patches on their bodices indicated they were participating in whatever this miserable rain-soaked Saturday morning had going on. “What’s happening,” I asked. “Is this some sort of race?”

“We’re raising money and awareness for Carkeek park, Pipers Creek, and the salmon habitat,” said one of the teenagers.

“Is it a race?”

“Not exactly. We signed up for twelve hours. Some people signed up for six.”

“You are doing this loop over and over again for twelve hours?” I glanced at my watch. It is 2:30. “When did you begin?”

“Seven. We might quit soon.”

They gave each other sideways glances as though they had both been thinking this but hadn’t spoken aloud until pressed by a stranger. I thanked them for their commitment. Full of gratitude for what these girls were doing, I continued to the wetland, the beach, and back to the salmon hatchery.

These people were Carkeek Park Salmon Stewards. I counted a dozen or so. Their intention: to maintain a fish-friendly pollution-free environment throughout the entire area that drained into Pipers Creek and Puget Sound. Within the dense forest on the trail, all human habitation disappeared but, on the rim, buses ran along the road at the back of a large strip mall, houses with their well-tended gardens edged on this old homestead turned wilderness. Their goal is to provide members of their community the wherewithal, motivation, and experience necessary to change their everyday behaviors in pursuit of healthy area salmon and salmon habitat.

Seattle is home to six other watershed restoration projects. Municipalities to the north and south are engaged in cleaning up many more watershed catchment streams that feed into Lake Washington, Lake Sammamish, and Puget Sound. A quick google search indicates that watershed awareness and restoration projects thrive in many other countries.

What about you and me? Do we feel the pull of water on the place where we live? I am not sure what impulse from my childhood, or my ancestry made me so acutely aware of how I relate to my environment. For as long as I can remember, I have known where the nearest body of water was and how my home related to it—or failed to relate to it. This natural affinity for daily physical connection was not conscious until it did not exist.

In 1997 after the death of my first husband of thirty-five years, I moved into a little Tudor brick house in Maple Leaf. I felt unmoored and alienated there, unable to find my ground or the path water took when it fell on my plot of land. A six-lane interstate highway sliced through natural streamlets that may have flowed to Greenlake.

Have you ever felt airborne, untethered? I lived in a high-rise in Belltown for several years after selling my Maple Leaf home just six months after I bought it. The condo had a balcony and access to a pea-patch garden on the sixth floor, but to get to soil with trees, under-story, spores, and micro-organisms that constitute a growing environment, I had to take an elevator and acknowledge a concierge, walk several blocks through concrete and steel. The nearest green area sheltered people in tents. I gave them wide birth when I entered their space, but enter I did.

I tried to make my peace with high-rise living. Urban density is good for the environment, but the body loses something fundamental to human existence when it loses touch with the earth. There are ways to compensate for this dislocation. Finding your personal connection to the ground takes intention and effort. It is not necessary to live on a piece of ground to connect with it. For me, it was necessary.

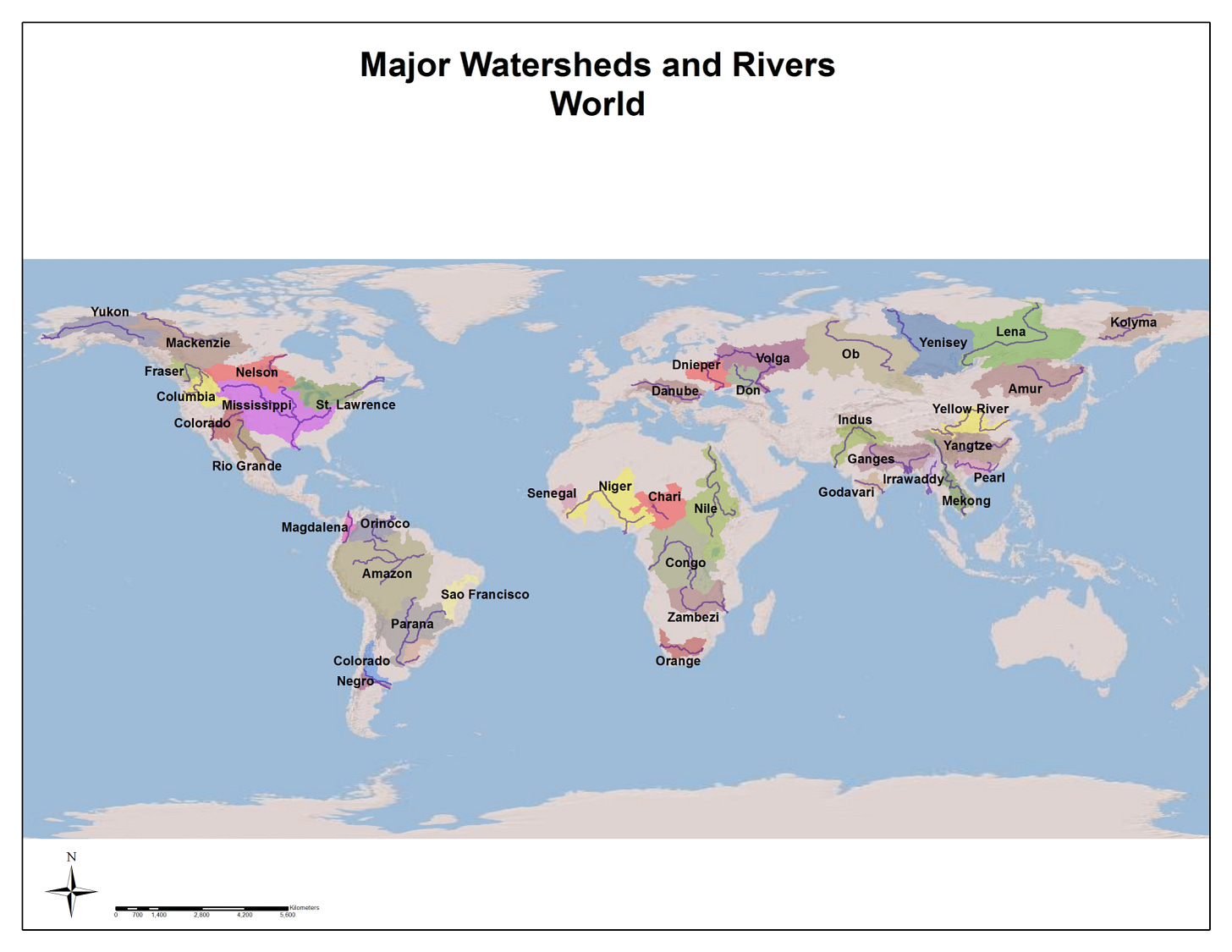

Why should we care? Because humans have for millennia lived connected to their watershed. Years ago, in college I had a professor who taught the history of Russia from the perspective of the people and their connection to the waterways, tracing the movements of prehistoric inhabitants up and down the river system flowing from the Urals to five large bodies of water. Patrick Manning, Professor Emeritus of the University of Pittsburg has found a way to convey humanity’s intimate connections to streams, rivers, lakes, and seas. He has designed a set of maps of the world to represent hydrology in the history of the past 10,000 years. You can trace the movement of Indigenous people in North America through river systems. As European settlers came to this hemisphere, they used the river systems to advance across the continent. Many developed deep roots in their new habitats, but most of our ancestors whether from Asia, Europe, India, or elsewhere left behind the water and land whose very DNA flowed through them

.

We steward what we love, care for it, and protect it for future generations. As Mary Oliver told Maria Shriver in an interview in 2011, “I am not very hopeful about the Earth remaining as it was when I was a child. It’s already greatly changed. But I think when we lose the connection with the natural world, we tend to forget that we’re animals, that we need the Earth.”

What better way to kindle that connection than to stand on the ground you call home and ask yourself, “What is my watershed?” If it isn’t obvious (you don’t live on a hill or next to the beach) get out a contour map, find your home in it and see what water is below your elevation.

When you realize the answer, you will find yourself attending to things like never topping up at the gas pump or pouring the dregs of a can of oil into the street. You may even connect emotionally with the peoples who called this land home before you. You may find yourself wondering what watershed your people came from before they migrated. We might argue that humans are more nomadic in the digital age than ever before, so the effort to ground ourselves in the watershed of every environment we visit, for a week or for years requires intention. Work from home and discover that “home” grounded in a specific geographic area. Know its hydrology. You will feel the blessing the Earth gives you.

Discover your watershed. It may change how you move and have your being.

P.S. The summer I turned seventy-five, I hiked the Engadine valley following the Enn river in southeast Switzerland. On the last day of our hike, we four seventy-five-year-olds reached Meloja Pass which divides the Danube and the Po watersheds. At that moment I felt a bodily connection to human history from where I stood to the mouth of the Danube in the Black Sea and to the mouth of the Po in the Adriatic Sea

.

Please share your watershed experience with me and my readers.

"Urban density is good for the environment, but the body loses something fundamental to human existence when it loses touch with the earth."

"But I think when we lose the connection with the natural world, we tend to forget that we’re animals, that we need the Earth.”

What's good for the environment, is harmful to people [in cities]. And when city dwellers lose connection to the Earth, we're less likely to consider the environment. Yikes. It's got my mind looping all over the place trying to sort that out.

I may have a new route down to The Sound these days but the walk all the way around Alki will always be my favorite.

Thanks for getting us thinking, Betsy.

Lovely! Thank you for sharing, Betsy.